Getty Images v Stability AI: What the High Court Did (and Didn't) Decide

Last Reviewed: 14 November 2025

Summary

The High Court has rejected Getty Image’s secondary copyright claim against Stability AI. Stable Diffusion’s model weights are not "infringing copies” under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 (CDPA).

The court accepted that an “article” for secondary infringement can be intangible (e.g. a model file in the cloud). But to be an “infringing copy” under s.27 CDPA, the article must at some point consist of or contain a copy of the work. Stable Diffusion never did.

Getty had already abandoned its core UK copyright claims about training and outputs, along with database right claims. This judgment does not decide whether training on third-party works outside the UK is lawful, or when AI outputs infringe copyright.

Getty achieved only very limited trade mark success: a small number of historic instances where early versions of Stable Diffusion generated images with Getty/iStock-style watermarks infringed under ss.10(1) and 10(2) Trade Marks Act 1994. The judge described that infringement as “extremely limited” and rejected all s.10(3) and passing off claims.

Technically, the judgment is important because the court engaged closely with a how a latent diffusion model works and held that model weights are “purely the product of the pattern and features” learned during training, not stored copies of the training images.

Practically, this is a significant win for Stability and the wider AI industry, but it is also narrow: training-stage copyright and “infringing output” claims remain very much alive for future cases, particularly where acts occur in the UK or evidence of memorisation is stronger.

Introduction

Getty Images (US) Inc & Ors v Stability AI Ltd [2025] EWHC 2863 (Ch) is the UK’s first major judgment on the interface between generative AI models and IP law. It has been widely reported as a landmark win for Stability AI, the company behind the Stable Diffusion image generator, and a setback for rightsholders.

That characterisation is broadly fair - but only if we are precise about what the court actually decided, and what remains undecided. Much of Getty’s original case fell away before judgment: key primary copyright and database claims were abandoned during trial. The court’s most detailed reasoning focuses on secondary copyright infringement and trade marks, not on the lawfulness of training itself.

Background

Getty’s starting point was simple to describe but complex to prove: Stability had allegedly scraped millions of Getty images (and their metadata) from Getty’s sites without consent, used them in training several iterations of Stable Diffusion, and then supplied a model that could output Getty-like images, sometimes even with Getty watermarks.

The pleaded claims were correspondingly broad:

- Primary copyright infringement in training and development (downloading and storing Getty images)

- Primary copyright and database right infringements in output (images generated by Stable Diffusion said to reproduce Getty works).

- Trade mark infringement and passing off, where outputs bore Getty or iStock-style watermarks.

- Secondary copyright infringement, on the basis that the distributed Stable Diffusion models were “infringing copies” under ss.22-23 and s.27 CDPA.

However, by the time judgment was handed down, the pleaded claims were significantly narrowed:

- Getty accepted it had no evidence that training and development took place in the UK. Given copyright’s territorial nature, the “training claim” was abandoned.

- Getty also dropped the “outputs claim” - alleged copyright and database infringement via specific watermarked outputs - after Stability blocked the relevant prompts, effectively delivering the injunctive relief Getty wanted.

What remained for trial was therefore much narrower:

- Secondary copyright infringement: was Stable Diffusion (versions 1.x, 2.x, XL and 1.6 an “infringing copy” within s.27(3), such that importing and distributing it via Hugging Face infringed ss.22-23 CDPA?

- Trade mark infringement under ss.10(1), (2) and (3) TMA, and associated passing off, based on the appearance of Getty/iStock-style watermarks in synthetic outputs.

How Stable Diffusion works - and why model weights mattered

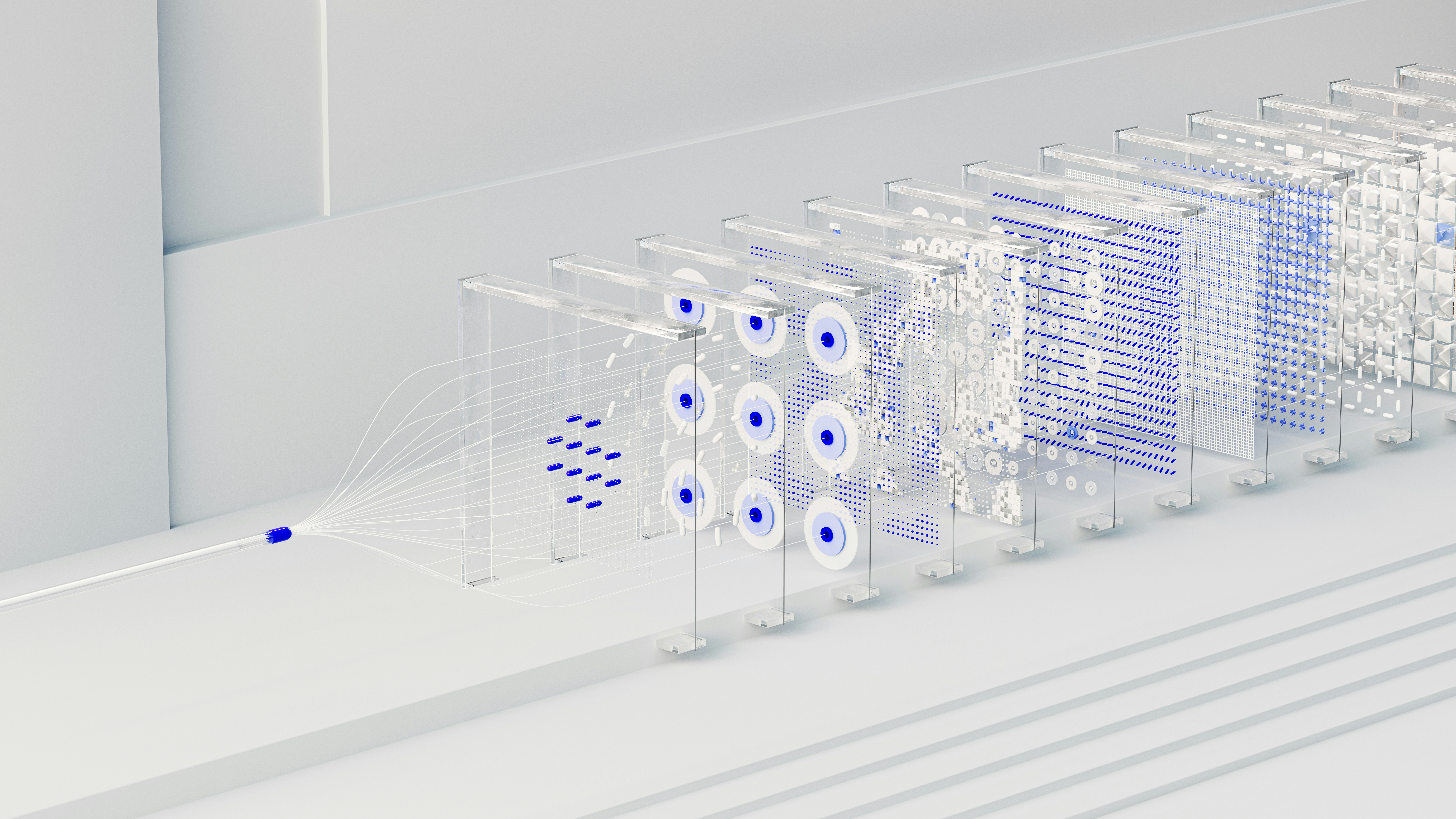

Mrs Justice Joanna Smith began by setting out, in accessible but technically accurate terms, how a latent diffusion model such as Stable Diffusion operates:

- Stable Diffusion uses a deep neural network with multiple layers.

- During training, the network is repeatedly exposed to huge numbers of captioned images scraped from the internet (including, Stability accepted “at least some” Getty images). The model weights - the numerical parameters that define the network’s connections - are updated iteratively to minimise a loss function.

- Once trained, inference is an input-output process: the user supplies a text prompt (or seed images), the model begins from random noise in a latent space and iteratively denoises to produce a new synthetic image consistent with the prompt. No training images are consulted during inference.

Crucially, the court accepted expert evidence - and both parties agreed - that the model weights do not store copies of any training images. They encode statistical relationships and features, not pixel data that can be reverse-engineered into the original works.

Secondary infringement and s.27 CDPA: why Stable Diffusion was not an “infringing copy”

“Secondary infringement” describes liability for dealing in infringing copies of a work - for example, importing, possessing in the course of business, selling or distributing them - even if you did not make the original infringing copy. In the CPDA, these are the acts covered by ss.22-26.

These provisions only bite if the thing dealt with is an “article” that is an “infringing copy” of a copyright work. Section 27 then defines when a copy is “infringing”, including where:

- the article is a copy of the work made without licence in the UK; or

- under s.27(3), the making of that article would itself have been infringing had it taken place in the UK.

Getty’s theory was that Stable Diffusion’s model weights were themselves the article: because training necessarily involved unlicensed copying of Getty images, the making of the weights would have infringed if done in the UK; therefore the weights were “infringing copies” and Stability’s making them available for download via Hugging Face amounted to secondary infringement.

Stability argued, among other things, that:

- “Article” in ss.23-23 should be limited to tangible objects; and

- in any event, a copy must contain or store the work (or a substantial part of it). A model that never contained copies of Getty images could not be an “infringing copy”, regardless of the training process.

Are model weights an “article”?

On “article” the judge sided largely with Getty. Applying the “always speaking” principle of statutory interpretation, she held that the term is not confined to physical items: an electronic copy stored in an intangible medium (such as model weights on cloud infrastructure) can be an “article” for ss.22-23 CDPA.

She also accepted that:

- Downloads of Stable Diffusion model weights to the UK devices amounted to “importation” for s.27(3) purposes; and

- providing API access via a hosted service such as DreamStudio, without transferring any copy of the model itself to the UK, did not constitute importation.

For AI developers, that is an important point in its own right: intangible software can be an “article” and its download into the UK is treated as importation.

What is an “infringing copy”?

The real action was on the meaning of “infringing copy”. Here, the judge accepted Stability’s core submission.

Starting from s.17 CDPA ('infringement of copyright by copying') and earlier authority on temporary copies in hardware, she held that an “infringing copy must be a copy”, i.e. a reproduction of the work, including by storage in any medium. An article cannot be an infringing copy “if it has never consisted of / stored / contained a copy” of the work.

Getty argued that this read words into s.27(3): in its view, it was enough that the making of the article involved infringement, even if the finished article no longer retained the work. But the judge rejected that construction, treating “infringing copy” as a composite phrase whose meaning is informed by the underlying concept of copying in s.17.

That analysis is closely tied to the model’s technical architecture. The judge found:

- While training Stable Diffusion did involve the reproduction and storage of Getty images on servers outside the UK,

- after training, the model weights do not store the visual information from those works; instead, “the model weights are purely the product of the patterns and features which they have learnt over time during the training process”.

On that basis, Stable Diffusion never “consisted of or contained” copies of Getty works, even transiently. It followed that:

- Stable Diffusion was not an “infringing copy” under s.27(3)

- ss.22 and 23 (secondary infringement by importation/possession/distribution of infringing copies) were not engaged; and

- Getty’s secondary infringement claim failed.

Trade mark findings

The trade mark claim concerned outputs where Stable Diffusion produced images with marks identical or similar to registered GETTY IMAGES and ISTOCK word/device marks - typically in the form of watermark-like text across synthetic images.

Two features of the court’s approach are worth highlighting.

Evidence: experiments vs “real world” use

Getty relied on:

- Litigation experiments: prompts crafted by its expert and lawyers (often based on Getty captions) to provoke watermark-bearing outputs from different model versions; and

- a much smaller set of examples found “in the wild”, generated by third-party users.

The judge was cautious about placing weight on experiments divorced from real-world usage. She placed particular emphasis on:

- whether there was evidence of UK users actually generating such outputs; and

- whether the prompts used (often highly specific Getty captions) were realistic proxies for how the average consumer would interact with the model.

This evidential scepticism drove much of the outcome.

Sections 10(1) and 10(2): limited infringement

After a detailed analysis of Getty’s registrations and the goods/services they covered, the judge held that providing Stable Diffusion was, in part, the provision of a synthetic image generation service falling within some of Getty’s class 9, 38 and 41 specifications.

On use of the signs, she rejected Stability’s attempt to characterise the watermarks as solely the act of users. Given Stability’s control over:

- the training data (including images bearing real watermarks),

- the model architecture and weights, and the

- code pathways that caused synthetic watermarks to appear,

Stability had done more than merely create the technical conditions for third-party use.

The court then compared specific examples of output watermarks with the registered marks. It found:

- For v1.x, two images with ISTOCK-style watermarks amounted to infringement under s.10(1) (double identity) and/or s.10(2) (likelihood of confusion).

- For v2.1, one image contained a blurred Getty-style watermark that was sufficiently similar to give rise to confusion under s.10(2).

However, there was no real-world evidence of users generating infringing watermarks using later versions (XL and 1.6), so those claims failed entirely.

The judge ultimately described the infringement she did find as “extremely limited” in scope.

Section 10(3): artefacts, reputation and economic behaviour

Under s.10(3), Getty argued that watermark-bearing outputs tarnished or diluted the reputation of its marks and that Stability took unfair advantage of that reputation.

The judge rejected the s.10(3) case in its entirety. Among other things:

- Getty produced no convincing evidence of a change (or likely change) in the economic behaviour of the average consumer, as required by recent authority.

- There was no substantiated real-world evidence of watermarks appearing on violent or pornographic imagery such that reputation damage could be inferred.

Importantly for AI practitioners, the judge also engaged with Stability’s argument that many of the alleged “watermarks” were simply visual artefacts of the generative process - distorted, incomplete or “off” badges that a reasonable user would not read as trade marks at all.

In a key passage she rejected Stability’s attempt to generalise that argument, holding that while some marks were clearly broken, others were not. For those clearer examples, the average consumer would not view the marks as “purely the artefacts of the image synthesis process rather than the purveyors of some commercial origin message”.

The passing off claim was effectively parked: given its thin pleading and overlap with the trade mark issues, the judge declined to make separate findings.

What the judgment does not decide

Given the case management history, it is essential not to over-read this decision.

The court did not decide:

- whether training an AI model on copyright-protected works is itself infringing as a matter of UK law, where that training occurs in the UK; or

- when, and to what extent, AI-generated outputs that resemble training images infringe copyright or database rights.

Those issues fell away because of territoriality (no UK training acts) and Getty’s strategic decision to drop the outputs claim once Stability blocked relevant prompts.

The court did, however, hear expert evidence that “memorisation” and “overfitting” can lead a model to reproduce training images in some circumstances, particularly where data is duplicated. That evidence did not need to be applied to decide liability here, but it will be highly relevant in future cases focused squarely on outputs.

Looking ahead

Getty has not yet confirmed whether it will appeal, and related proceedings continue in the US, where questions of fair use and US territoriality will be centre stage.

For now, the UK position can be summarised (cautiously) as follows:

- Models are not infringing copies merely because they were trained on infringing data, especially where training happens outside the UK and the resulting model weights do not store the works.

- Rights holders seeking to challenge AI tools will need strong, fact-specific evidence – of UK-based acts, of memorisation, or of concrete trade mark harm - rather than broad policy arguments.

- The real battlegrounds are likely to be future cases focused squarely on training in the UK and cases with stronger evidence of infringing outputs, alongside regulatory and legislative reforms to copyright and TDM exceptions.

In that sense, Getty v Stability AI is both a major decision and an opening move. It tells us a lot about how English courts will reason through AI-specific copyright and trade mark questions, but it leaves many of the hardest issues still very much in play.